This post is from Petteri Impola, a doctoral student and member of Early Modern Morals – a research center at the Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä. His thesis-in-progress entitled: “The Agency and Intangible Capital on the Edge of Estate System in Sweden during the Age of Greatness (c 1620–1720)”, examines the connections of agency, work, and estate and social status in 17th century Sweden. The focus of the thesis is on types of agency that were not attached to one single estate status in early modern everyday life, even though estate-based society and the profession privileges associated with it ideally demanded a strict distribution of work.

Petteri Impola (University of Jyväskylä)

Estates formed the foundation of most societies in early modern Europe. In Sweden, for example, it was the four estates that formed the basis of the society: the nobility, the clergy, the burghers, and the peasants. These categories functioned as legal and political hierarchies, but were also essential in the process of distributing work. Most of the privileges employed to regulate work and trade in mercantile societies were based on statuses derived from the estate-based order.

Even if the distribution of work was in general based on estates, certain professions were carried out by individuals belonging to different estates and of different social statuses. Trade, for example, was traditionally the privilege of the burghers but was practiced, though illegally, by agents from all of the estates. There were also forms of agency, like legal representation, which was not privileged to one estate, and every capable man could participate. Moreover, certain groups of people remained outside the formal estate-structure, as is the case with groups such as vagrants and soldiers. Hence, a significant amount of early modern work took place on ‘the edges of the estate-based order’.

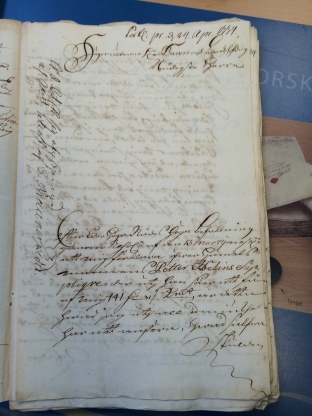

Therefore, in my thesis I examine early modern agency not just from the perspective of gender but also by the intersections of estate position and social status. I compare three different (semi-)professions, which cannot be explained through estate-based privileges: cunning folk, self-educated midwives, and legal representatives. Legal representation, for example, was an emerging profession because of the developing legal system, and almost every man with some reading, writing, and legal skills could help others in the courts. There were sons of clergy and burghers, soldiers, clerks and other low-level civil servants and even peasants working as representatives. The skills and reputation of the agents were crucial for their agency, not just their ancestry. Continue reading “Court record books as a source for early modern agency and work”