This post is written by Bob Pierik who is a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam. He is part of the NWO (The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research) project ‘The Freedom of the Streets. Gender and Urban Space in Europe and Asia 1600-1850.’ Earlier this year he started a dissertation project on the gendered use of urban space in early modern Amsterdam.

Bob Pierik (University of Amsterdam)

In March 1710, ordinary life at the Amsterdam Botermarkt was disrupted when Grietje Veenendael, who had a market stand with stockings, was attacked by another market woman. The two women had a dispute over the location of their market stands after which Lena (last name unknown) pulled Grietje backwards and threw her on the ground. Lena’s two daughters and the husband of one of them joined the fight and kicked Grietje brutally.

After the violence, when Grietje had fled to the chief officer to make a statement, people gossiped in the market that a man had attacked Grietje. Perhaps this happened because of the presence of Lena’s son-in-law. Nevertheless, one of Lena’s daughters then returned to the scene to dispel those rumors. She told bystanders ‘while beating her chest’ that ‘it was no man who did that, but me and my mother.’[1]

In my research, I am trying to get a sense of embodied practices of gendered use of urban space. The above is a case that I was able to reconstruct through witness statements drawn up by the secretary of the Chief Officer, who was also sworn in as notary. It is a conflict arising over the claiming and using of space in an area with large numbers of women present. The witnesses that reported the story of Grietje’s assault were all women, the only man present in the narrative was Lena’s son-in-law, which is remarkable compared to similar cases. It shows the textile market as an urban space dominated by women.

Furthermore, the source gives us a sense of the rumors that spread about the presumed gender identity of the attacker and there is the theatrical claiming of the violence by a woman, as a woman. Was she protecting her husband, who may perhaps have been prosecuted more harshly for attacking a woman than the daughter and mother? Or was she claiming the violence proudly as her own, as victor in a conflict over ownership of the streets?

Such cases containing very explicit gendered discourses and performances directly relating to the question of ‘who owns the street?’ are very insightful, but also somewhat rare. If we take the general narrative of this type of source as the main prism through which to look at the streets of Amsterdam, we get an image of streets dominated by men who engage in constant (knife) violence against each other. Women feature, but mostly as victims or witness. Besides some exceptionally informative conflicts that are explicitly about restriction or permission of someone’s presence, many violent conflicts are itself less revealing about ‘ownership of the streets’ and its more subtle negotiations.

However, we can leave the actual crimes to historians of crime and pay less attention to the conflicts that were the reason for the document to be drawn up. Rather, in the project that my research is part of, we want to look at the activities that were taken on by those individuals reported in the document. This allows us to reconstruct a snapshot of the situation before the disruptive event. By moving the conflict to the background, the background of the conflict moves to the forefront. This, the ‘pre-crime scene’, then forms my ‘field work’ for what I suggest can be called a form of historical urban ethnography. In many cases involving the Amsterdam notary archives, it is possible to reconstruct scenes in which we find all the persons mentioned in the attestation, before the ‘normal’ situation was disrupted and they were transformed into witnesses, perpetrators and victims.

From the perspective of the history of work, this approach is inspired by the ‘verb-oriented method’ developed by the Gender and Work Project Group at Uppsala University, which focuses on descriptions of practices of work rather than occupational titles.[2] From the perspective of cultural history, it is inspired by historians of the body that have called for a closer focus on practices in the form of a ‘praxiography.’[3] Historians of the body and ethnographers have used this approach to move ‘beyond interpretations of the body to the actions of physical bodies in practice.’[4] In similar vein, such an approach can be used to move beyond interpretations of space as characterized statically (e.g. public/private, male/female) towards space as constituted in practice by its users.

Many events can be given a specific location, often at least on the level of street names, but also frequently with remarkably more exact details. This allows us to study the role of women and men moving through the streets, chatting in front of houses, peeking through windows and sitting in backyards, but of course also: working, selling, trading, and providing lodging. This reveals practices of women and men and their interactions and actions.

This is not just an issue of historical geography, but it is very relevant for debates on gender and work as well. Work is very important here, because a large part of the gendered ideologies and expectations around work is spatial in nature. With these sources, we have potentially extensive quantities of empirical material to test theories that assert that the early modern period saw a separation of (gendered) spheres, a divide between the workplace and the home, and whether or not a ‘cult of domesticity’ surfaced. Among others, I hope that this method can enable us to investigate the locational and embodied aspects of work, leisure and consumption.

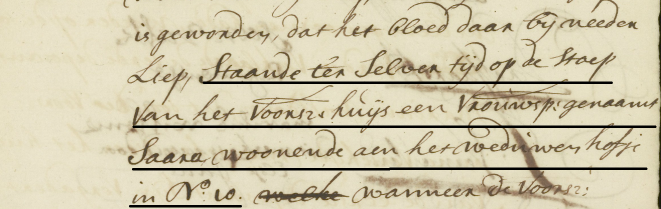

[1]Amsterdam City Archive (NL-AsdSAA), Archief van de Notarissen ter Standplaats Amsterdam, inv no. 8068: Minuutacten Gerard van Esterwege, 101.

[2] Rosemarie Fiebranz et al., “Making Verbs Count: The Research Project ‘Gender and Work’ and Its Methodology,” Scandinavian Economic History Review 59, no. 3 (2011): 273–293, https://doi.org/10.1080/03585522.2011.617576.

[3] Iris Clever and Willemijn Ruberg, “Beyond Cultural History? The Material Turn, Praxiography, and Body History,” Humanities 3, no. 4 (October 9, 2014): 546–66, https://doi.org/10.3390/h3040546.

[4] Clever and Ruberg, 553.